Nature & Architecture - 3 Design Approaches that Blur the Lines

/The relationship between architecture and nature cycles from harmony to defiance over and over again throughout the history of construction. Do we work with nature to build something complimentary, something organic? Do we minimize impact and disturb as little as possible? Or do we conquer the land and build monuments to our achievements? Depending on who you ask, the answers to these questions are polarizing. Because the philosophies and subsequent works of architects and designers are so diverse, there are varying opinions about what constitutes as good design as well as “natural” or organic architecture.

So let’s look at three predominant styles of architecture that attempt to exist in harmony with nature:

- Organic architecture: Originally coined by architect Frank Lloyd Wright as early as 1908, organic architecture is the reinterpretation of nature’s principles by man. People often confuse the term “organic” with the idea of something that looks like a plant or animal, but applied to architecture the meaning is more distilled. It is a respect for materials, which are sourced locally and used in a way true to their properties. It is the relationship of form and function, where Wright proclaims “form and function are one”, which is a variation of his mentor Louis Sullivan’s slogan “form follows function”. It is governed by a strict set of natural geometries. Finally, organic architecture is the attempt to marry site and structure, respecting the context and developing an intimate relationship between the two. While the style is defined by Wright’s work in the early 1900s, I’d argue that the earliest forms of habitable spaces could be considered organic architecture, including construction in the Neolithic period.

Samples of Organic Architecture:

There are so many gorgeous examples of organic architecture, but this should be enough to illustrate the typology. Let’s move on to the next, nature-architecture blend style.

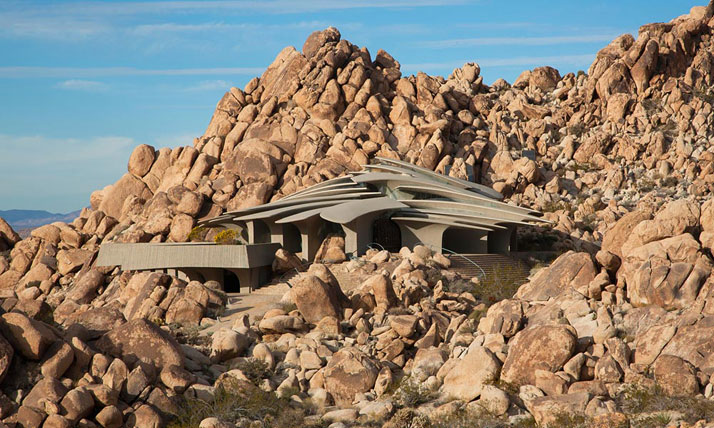

- Invisible architecture: Where organic architecture celebrates natural materials, form, and function, invisible, or camouflage, architecture attempts to hide the building altogether, placing total focus on the existing natural surrounding. Whether it be by strategic or protective means, like cave dwellings or hidden forts, or simply to preserve and enjoy nature, as in submerged and masked applications, these buildings may not look natural on their own but when placed within their particular context, they all but disappear.

Samples of Invisible Architecture:

And finally, one of the most contemporary architectural philosophies attempting to blend nature with structure is:

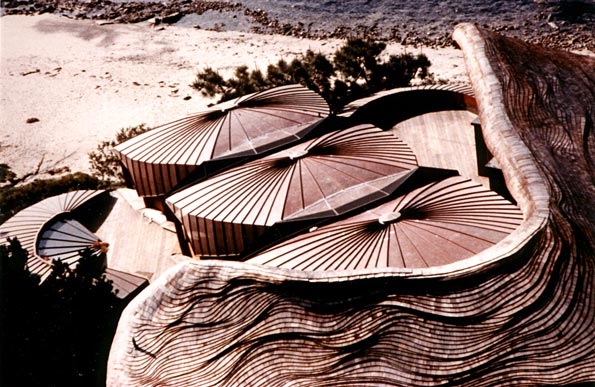

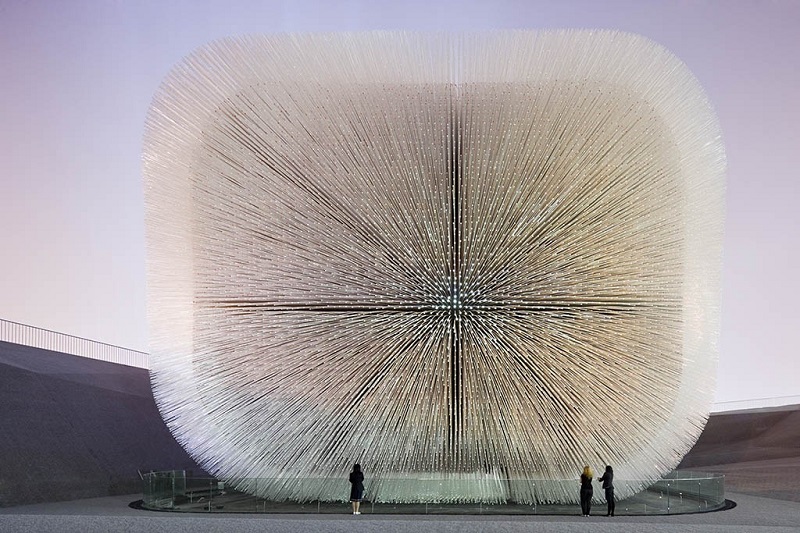

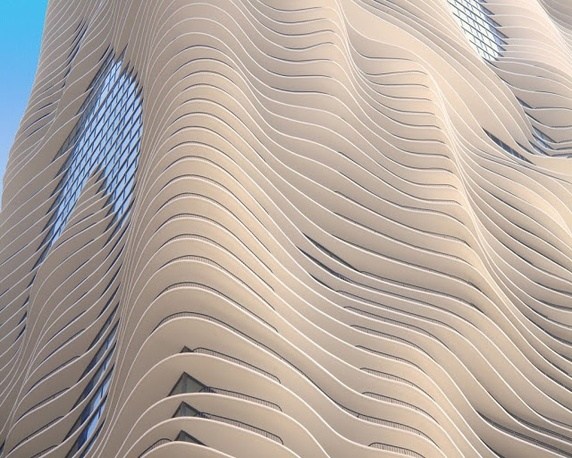

- Biomimetic architecture: This form of design moves beyond just emulating and celebrating natural forms and materials. Instead, it serves to mimic the way nature solves complex problems, such as heating and cooling needs, providing resources, or developing healthy communities. Biomimetic architecture imitates life, it behaves like nature, and seeks to become a living being. This architecture isn’t defined by being made of nature, honoring nature, or hiding within nature. Biomimicry fits within the natural world because it is man’s version of nature.

Samples of Biomimetic Architecture:

Because this is a relatively new trend, many examples of biomimetic architecture have yet to be built (a quick search of the term yields pages of breathtaking conceptual designs). But with booming advancement of materials engineering and precise, custom fabrication we’ll see many more of these living structures joining our landscapes in the near future.

While the philosophy and intent of each of these strategies is slightly different from the next, none are mutually exclusive. If you were to ask me, well designed buildings compliment, work with, draw from, and enhance their immediate context (both natural and man-made) while respecting larger fields of consideration (most importantly, the dimension of time, including the current period, historical trends, and potential future evolution). The best architecture draws elements from each of the items above and creates a space informed by powerful social metrics, client and user needs, and fiscally responsible decisions. Great design is the mastery and balance of the broadest range of life’s variables, which includes the profound relationship with nature.

This piece is also featured on Quora, responding to the question: What are well designed buildings that make them look like they're part of nature?